On May 5 of this year, thousands of people across the country took part in marches, forums, community gatherings, and vigils, mourning and bearing witness to a relentless tragedy. Most people at these events wore red, and some bore a red handprint painted across their mouths–a symbol for the thousands of indigenous women over the years who have been murdered or gone missing.

Women like Hanna Harris, Kaysera Stops Pretty Places, Ashley Loring Heavyrunner and unfortunately many, many more.

Since 2017, May 5 has been set aside as a National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. May 5 is the birthday of Hanna Harris, a 21-year-old tribal citizen of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe who went missing and was found murdered on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in 2013. This day, in addition to grassroots advocacy efforts and recent films Say Her Name and Somebody’s Daughter (1492– ), have garnered broader public attention to the crisis

“I’m lucky enough that within my immediate circle I have not had anybody go missing. I’ve had cousins and cousins of cousins be murdered or go missing. It would almost be unbelievable to non-Native people to realize the prevalence of this issue,” said Trish Hurtubise. Hurtubise is a member of the Couchiching First Nation in Ontario, Canada and works as a genetic genealogist specializing in Indigenous cases. She recently assisted the DNA Doe Project in identifying an Indigenous woman who had been found murdered in 1980.

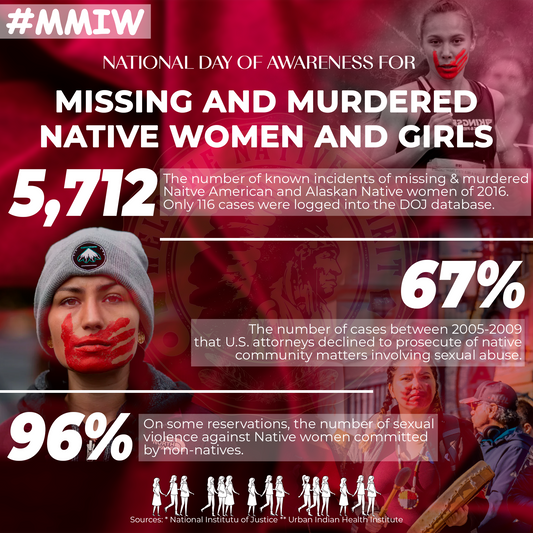

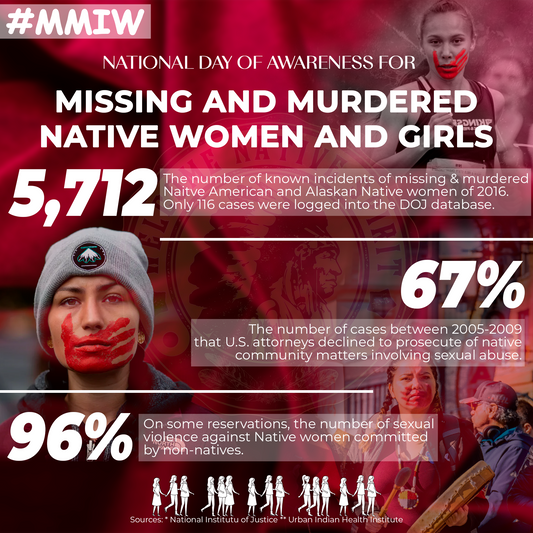

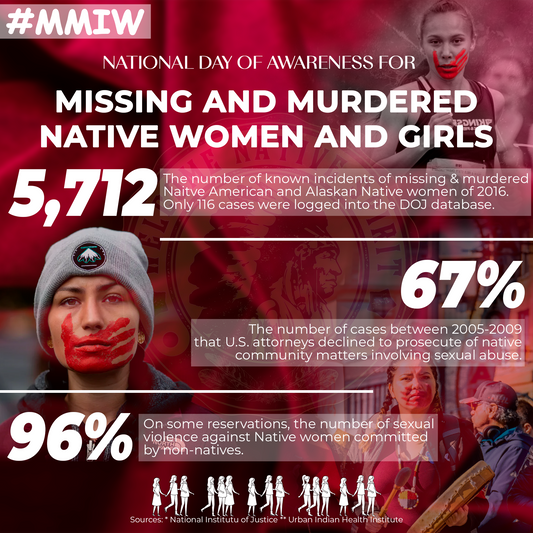

Of all groups in the United States, Native women face the highest rates of violence. According to data collected by the US Department of Justice, in some US counties the murder rates of Native women are ten times the national average. The same report reveals that Native women are almost three times as likely to experience rape or sexual assault compared to white, Black or Asian women. A report published in 2016 additionally suggests that interracial violence against Native women (and Native men) is more prevalent than intraracial violence, that is, most violent acts are committed by non-Native perpetrators.

National data on the number of missing Native women at any given time is hard to come by due to varied reporting requirements and the fluctuation of people going missing and being found again. However, the numbers that are available reveal some of the barriers to addressing the crisis. According to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), in 2016, there were 5,712 reports of missing Native women and girls, but only 116 of those cases had been logged into the NamUs database. Most of the collected data focuses on cases for reservation residents, but over half of people that identify as Indigenous actually live in urban areas, suggesting that these values are likely undercounted.

Ellie Bundy, the Presiding Officer of Montana’s Missing Indigenous Persons (MIP) Task Force, shared that Native women are about twice as likely to go missing in Montana compared to non-Natives. Bundy also serves as a tribal council member and Treasurer for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Indian Reservation.

The reason why this crisis of murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls exists cannot be traced to a single source, nor does it have a single solution. However, one major factor at play is the legal ambiguity and confusion regarding jurisdiction on cases that occur on tribal lands or involve Indigenous people. The pervasiveness of this crisis, in addition to the systemic structures that place Indigenous people in a position of vulnerability, represent to many a continuation of the violence Indigenous people have experienced for generations.

Who’s in Charge Here?

When a person is reported missing or when a body is found, the first 24 to 48 hours of the subsequent investigation are critical. However, when the individual in question is Indigenous or if the body is found on tribal land, the jurisdictional authority depends on several factors. Determining the nature of the crime, the race or ethnicity of the victim and perpetrator, and the location where the crime took place all delay investigations.

“When a person goes missing, it often isn’t known whether it’s related to a criminal act. Figuring out if there is a link to a crime and then identifying who should investigate it takes time,” wrote Bundy in an email.

The US Constitution grants the federal government the right to jurisdiction over crimes committed in Indian country where no congressional grant of jurisdiction to state government over the Indian country involved exists. Within the federal government, the BIA holds these responsibilities.

Some of the major legislation and legal rulings that grant states jurisdiction are the Major Crimes Act, the General Crimes Act and Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe (1978). In Oliphant, the US Supreme Court ruled that federally recognized tribes do not have the jurisdictional authority to prosecute non-Indigenous people for crimes committed on tribal land. Additionally, there are six states (California, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oregon, Wisconsin and Alaska) that are governed by Public Law 280, which gives the state criminal jurisdiction in all crimes committed on reservation land.

A poster from the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center (NIWC) outlines the complexity of this jurisdictional question (Table 1). “Major Crimes” refers to crimes outlined in the Major Crimes Act, which include murder and sex crimes under Chapter 109A.

Source: NIWC.

Furthermore, the legal question of jurisdiction is still very much in flux. For example, the US Supreme Court recently expanded state jurisdiction over crimes committed in Indian Country. In the case of Oklahoma v. Victor Manual Castro-Huerta (2022), the court granted the state of Oklahoma (which is not governed by PL-280) jurisdiction of crimes committed by non-Indian perpetrators against Indians in Indian country .

“We have families in the state who have had to conduct their own investigations while waiting for a jurisdiction to own their case and work it,” wrote Bundy. “That is absolutely unacceptable on every level.”

Beyond the complex question of jurisdiction, however, legal authorities also must choose to open, investigate and prosecute cases. Furthermore, as Bundy points out, many of the people who are reported missing live in isolated, remote areas and law enforcement agencies often lack sufficient resources. As a result, victims and their cases fall through the cracks.

What is Being Done?

Thanks to tireless advocacy work and increasing public pressure and awareness, the US federal government has taken several steps to help address the murdered and missing indigenous women and girls (MMIWG) crisis.

First passed in 1994, the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) was one of the first pieces of comprehensive federal legislation that acknowledged sexual assault and domestic violence as crimes and was designed to protect women from violence. VAWA is up for renewal every five years, with successive reauthorizations often improving and expanding upon the act’s existing programs and protections. The 2013 reauthorization included provisions for crimes that occurred on Tribal lands. The latest reauthorization from 2022 expanded jurisdiction of Tribal courts over non-Native perpetrators on tribal lands, increased support for survivors of violence, including LGBTQ+ individuals, and reauthorized existing VAWA grant programs.

Congress has also passed a few acts in recent years that offer more targeted support in addressing the MMIWG crisis. Savanna’s Act was passed in 2020 and aims to improve coordination between law enforcement agencies in cases of missing or murdered indigenous persons. The act was named after 22-year-old Savanna Lafontaine-Greywind, a member of the Spirit Lake Nation, who was murdered while eight months pregnant. In 2021, the Not Invisible Act was passed, mandating the formation of a commission to investigate ways to reduce violent crimes against American Indians and Alaska Natives. Also in 2021, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland announced the formation of a Missing and Murdered Unit within the BIA that will help lead and coordinate federal investigations of MMIP cases.

At the local level, many states have implemented MMIP task forces. The Montana MIP task force that Bundy serves on holds community listening sessions, provides testimony in relevant upcoming legislation, works to educate community and law enforcement members, and more.

A lot of this work involves educating Native peoples about the risks they face and equipping them with the knowledge to protect themselves and each other.

“I have only presented to one high school so far, but the experience made me realize that I need to get into all of our reservation schools,” wrote Bundy. “About 10 students approached me after to thank me and share that they had no idea about the reality of this, one even stating ‘Those girls you shared stories about were just like us.’”

On an individual level, there are also people taking steps to support safe and whole Indigenous communities, who find themselves not only facing the current injustices of the MMIWG crisis, but also the ripple effects of past injustices that separated Native peoples from their families and tribes.

Hurtubise started her work as a genealogist when searching for her half-brother. He had been separated from their family during Canada’s “Sixties Scoop”, a series of government policies, including residential schools, where Indigenous children were placed in non-Native families. Similar schools were setup in the US to remove Indigenous children from their families and cultural influences. Using genealogical tools and online DNA databases, Hurtubise managed to identify and reconnect with her half-brother. She now specializes in using genetic genealogy to help connect other Indigenous families.

Last year, Hurtubise launched Indigenetics, a non-profit aimed at expanding representation of Indigenous profiles in genetic databases. Since the organization is predominantly supported through volunteer efforts, Hurtubise has been sewing and selling ribbon skirts to help fund a group website, informational mailers and DNA ancestry kits.

As a frequent user of genetic databases in her work, Hurtubise notes that current databases are in a woeful state when it comes to representation of Indigenous people. Often, Native profiles are lumped in with other racial and ethnic groups, like Hispanic or Pacific Islander. She also encounters a lot of mistrust when encouraging other Indigenous people to submit samples to these databases. Some legal rights for Indigenous people, freedom of movement, for example, are intimately tied to genetic identity and are contingent upon an individual’s ability to prove their percentage of Indigenous blood is at least 50%. The people Hurtubise talks to are concerned that adding their genetic data to these databases could potentially be used against them to take away those rights.

Hurtubise’s hope is that these profiles will help connect separated families and identify remains from residential schools and missing persons cases. Identification of these remains can offer answers for grieving families and communities and help bring closure and healing.

For those within the forensics community, Hurtubise urges: “Create safe spots for people to do their tests and become an ally to this battle of identification. Take on cases. We’re identifying remains that have been found, but there are going to be future remains. We’re dealing with past, present and future right now, and it’s a monumental task and it’s a monumental sadness.”

![[Two Sides] No One Is Illegal On Stolen Land. We Walk On Native Land - Two Sides Unisex T-shirt/Hoodie/Sweatshirt](http://welcomenativespirit.com/cdn/shop/files/il_794xN.6684841969_tbob_533x.jpg?v=1768526723)

![[Two Sides] No One Is Illegal On Stolen Land. We Walk On Native Land - Two Sides Unisex T-shirt/Hoodie/Sweatshirt](http://welcomenativespirit.com/cdn/shop/files/Mockup3_533x.jpg?v=1768526723)

![[Two Sides] No One Is Illegal On Stolen Land. We Walk On Native Land Style 2 - Two Sides Unisex T-shirt/T-shirt V-Neck/Hoodie/Sweatshirt](http://welcomenativespirit.com/cdn/shop/files/6_2_533x.jpg?v=1741146815)

![[Two Sides] No One Is Illegal On Stolen Land. We Walk On Native Land Style 2 - Two Sides Unisex T-shirt/T-shirt V-Neck/Hoodie/Sweatshirt](http://welcomenativespirit.com/cdn/shop/files/16_f80c6325-e0fb-4531-9139-416ef6578037_533x.jpg?v=1741146782)

![[Two Sides] Trail of Tears The Deadly Journey Unisex T-shirt/T-shirt V-Neck/Hoodie/Sweatshirt](http://welcomenativespirit.com/cdn/shop/files/20_2bae9cf5-c07c-4ea5-a8ea-de74aa71325d_533x.jpg?v=1757466962)

![[Two Sides] Trail of Tears The Deadly Journey Unisex T-shirt/T-shirt V-Neck/Hoodie/Sweatshirt](http://welcomenativespirit.com/cdn/shop/files/gray_-2side_b51af6c7-cea9-4004-90db-cb8d883be04a_533x.png?v=1759742586)